I know that last week, we did a showdown of Sondheim vs. Lloyd Webber, and so doing another expose of a Sondheim production might be overkill. Yet, it’s Halloween week, and what better theme than something as dark and creepy as Sweeny Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street?

Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street, is a story whose macabre tentacles have crept across the centuries, morphing from Victorian penny dreadful to operatic stage musical to darkly stylish film. In the world of horror musicals, few works have simultaneously chilled and enthralled as powerfully as Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd. Central to Sondheim’s vision are horror elements articulated not only through plot and character but through music, staging, lighting, even the sickle-like shape of a barbershop razor. The tale has found two particularly iconic manifestations for a broad audience: the stage musical immortalized in the performance of Angela Lansbury and the 2007 movie adaptation starring Johnny Depp, directed by Tim Burton. Each brings a unique grimness, playfulness, and psychological depth to the ghastly legend—a difference shaped by choices in themes, lighting, sound, music, lyrics, and the ultimate crafting of terror.

This post embarks on a detailed, analytic journey through the horror elements of Sweeney Todd, with an intensive comparative lens on the Lansbury musical, where Angela Lansbury originated Mrs. Lovett and Depp’s film, where the legendary actor took on the role of Sweeney Todd himself. We’ll dissect the various components—narrative thematics, lighting and visual palette, ambient sounds and design, composition and orchestration, the lyrical machinery, and, finally, the overarching horror atmosphere. By examining how each catalyzes dread, black humor, and emotional catharsis, we’ll see how Sondheim’s vision has proven uncannily adaptable to both the epic stage and murky celluloid.

Thematic Foundations: Horror in Narrative and Character

The Johnny Depp Film: Obsession, Madness, and Bleakness

Tim Burton’s 2007 film adaptation of Sweeney Todd foregrounds horror by plunging the audience into a world drained of color—both literally through its desaturated cinematography and figuratively through relentlessly bleak themes. This incarnation is, above all, a tragedy of psychological obsession. We are introduced to Benjamin Barker, reborn as Sweeney Todd (Johnny Depp), whose quest for vengeance against Judge Turpin isn’t just personal retribution but a consuming mania that rots his soul. The horror resonates through Todd’s transformation: an ordinary man, brutalized by injustice, who disassociates from all human feeling except his need for revenge. His world is a “great black pit,” an image that becomes reality in both his mind and the soot-choked London around him.

Unlike the more sardonic or satirically grand approaches, Burton’s film leans heavily into Gothic melodrama and violence. Characters are painted with broad, dark brushstrokes; Turpin is a truly monstrous villain, and Mrs. Lovett (Helena Bonham Carter) is a tragic, damaged opportunist. The undercurrent of loss and futility supplies a horror both psychological and physical: vengeance never brings satisfaction, and innocent suffering proliferates. Notably, the film sharply downplays the comedic and Brechtian distance present in the stage version, resulting in a work thick with existential gloom.

The Angela Lansbury Musical: Grand Guignol, Satire, and the Human Condition

In contrast, the Angela Lansbury stage production (and its filmed version with George Hearn) frames its horror with a distinct sense of black comedy and social critique. Director Harold Prince envisioned Sweeney Todd as an allegory for the dehumanizing march of the Industrial Revolution—a world that manufactures people as efficiently as it chews them up. Sondheim’s score and Hugh Wheeler’s book present Todd not only as a victim and monster but as a cog crushed by an uncaring system. Judge Turpin’s corruption is a stand-in for the abuses of power endemic to Victorian (and, by extension, modern) society.

This approach makes Mrs. Lovett, in Lansbury’s hands, a figure of deranged, music hall charm. Her comedic persona lessens the overt horror, but the cheerful practicality with which she proposes baking human pies is, if anything, more chilling in its normalization of atrocity. The musical’s tone is an uneasy mixture: horror is played for laughs, but the underlying message is never lost—this is a society where exploitation and cannibalism are literal and metaphorical.

Furthermore, the Lansbury version uses the chorus—a Greek chorus that directly addresses the audience via “The Ballad of Sweeney Todd”—to maintain an awareness of the tale as a cautionary horror fable. Unlike the film, which immerses the viewer in the tragedy, the musical often breaks the fourth wall and invites audiences to meditate on its moral ambiguities.

Lighting and Visual Atmosphere

Tim Burton’s Cinematic World: Bleakness Encased in Shadow

Tim Burton’s cinematic signature is unmistakable. The world of Depp’s Sweeney Todd is London as a haunted funhouse: drained of color, thick with fog, and saturated with sinister shadows. The color palette is dominated by steel, charcoal, and muted blues, interrupted only by the surreal vibrance of arterial blood—a visual motif both shocking and ritualistic.

Burton uses sharp contrast: interiors are under-lit, faces half-shrouded, eyes shadowed. The film’s omnipresent gloom is sometimes spiked by harsh spot or strip lights—illuminating razors, white hands, and ghoulish expressions. Dariusz Wolski’s cinematography brings a cold, claustrophobic intensity, making the viewer feel trapped alongside the characters. The notorious red of blood is almost hyperreal, standing out grotesquely in the near-monochrome environment, as if color only exists in violence. Scenes such as Mrs. Lovett’s fantasy “By the Sea” burst into a grotesque parody of Technicolor cheer, sharply juxtaposed with the surrounding squalor.

Visual effects, including digital set extensions, create a London that is artificial yet oppressive—almost a character in itself. The film’s abstracted, nightmarish cityscape enhances the sensation of dread and otherworldliness, solidifying its horror credentials.

Stage Lighting in Harold Prince’s Production: Expressionist Contrasts and Theatricality

On stage, Sweeney Todd employs a different, but equally disturbing, visual strategy. Prince’s original Broadway set—massive, industrial, with moving iron bridges—emphasized the mechanistic, oppressive qualities of Victorian London. Lighting designer Ken Billington and scenic designer Eugene Lee played with chiaroscuro, using cold white spotlights, deep shadows, and pools of light to isolate characters, underscore violence, and build tension.

Lighting in the Lansbury musical exploits warm and cool color temperatures to mark emotional states. Key “hot” moments—murders, Todd’s epiphany—are lit with harsh amber or even red, evoking both fire (the fire of revenge) and blood. “Cool” moments—scenes of plotting, reflection, or fleeting tenderness—employ blue or moonlit washes, creating a liminal space suggestive of emotional distance or numbness.

Theatrical techniques such as silhouette, shadow play, and quick “blackouts” are frequently employed to mask transitions, heighten suspense, or present violence through suggestion rather than explicit depiction—a necessity due to technical and safety limitations but also effective in preserving an environment of dread. The choreography of light is often as crucial as the movement of actors: a spill of white emphasizes a razor, an isolated shaft picks out Todd’s haunted face in the dark.

Ambient Sound Design: Building a World of Dread

Film Adaptation: Cinematic Soundscapes and Subterranean Tension

In Burton’s Sweeney Todd, ambient sound is a character in itself. The sound design does not simply situate us in Victorian London; it traps us there. From the opening, we hear the low, industrial grind of factory machinery, distant ship horns, and omnipresent rain. Prison sounds, streetcar clatter, marketplace shouting, ominous church bells, and the sharp gleam of razors swishing through the air all contribute to a dense, oppressive aural world.

Burton is unafraid of silence, using it not as a respite but as a void—a momentary loss punctuated by sudden, shocking noises (the hiss of a blade, the dull thud of a corpse). The blood fountains and gory moments are often emphasized with hyperrealized sound effects, making even non-visual moments queasily visceral.

Diegetic and non-diegetic sounds blend: music often emerges from everyday noise, the line between musical number and sound design blurred to sharpen immersion and tension. Surround sound and spatial mixing are used to envelop the viewer, placing us directly in Mrs. Lovett’s foul-smelling kitchen or Todd’s echoing barbershop.

Stage Musical: Live Orchestration and Theatrical Sound Effects

The Angela Lansbury musical, especially in large-scale productions, marshals the live orchestra as both score and ambient effect. Sondheim’s music frequently mimics industrial noises—hissing pipes, churning gears—through the use of harsh strings, percussive effects, and dissonant orchestration, reinforcing the machine-like environment of the metropolis.

Live sound effects—steam whistle blasts for murders, floorboards creaking in darkness, and the crash of trapdoor mechanisms—are carefully timed to create surprise and unease. The absence of realistic foley (e.g., blood splatter, bone-chop) means that violence is often rendered more through musical punctuation and audience imagination than explicit sound.

Ensemble singing often functions as an ambient backdrop. The chorus, with its chanting and humming, becomes the very “sound of the world out there” referenced in the script. The opening “Ballad of Sweeney Todd,” with its whispering sibilants, conjures the impression of a swarm or a gathering storm, immediately unsettling the audience on a primal level.

Orchestration, Score, and the Engine of Dread

Sondheim’s Score: A Framework for Horror

Sondheim reportedly conceived Sweeney Todd’s score with horror film music in mind—particularly the suspense-laden work of Bernard Herrmann for Alfred Hitchcock. In both the film and Lansbury musical, over 80% of the drama is sung or underscored by music, a rare intensity that pushes the show toward operatic territory.

At its heart are recurring motifs and the ancient Dies irae theme, an omen of death and justice found in the Latin requiem mass. The musical’s “Ballad” is built on these motifs, cycling in and out, sometimes inverted harmonically—a musical realization of unending vengeance. Leitmotifs for Sweeney, Lovett, and even the city animate the score, signaling character psychology, impending violence, and moments of black humor.

Film Score: Cinematic Expansion and Intimate Restraint

For the film, orchestrator Jonathan Tunick expanded Sondheim’s relatively compact stage orchestra to a 78-piece symphonic array, leveraging lush strings, swelling brass, and the full dynamic range of Hollywood soundtracks. This broader palette lends the film gravitas and scale, while intimate scenes are supported by minimalist, close-miked arrangements—the resulting effect more claustrophobic than ever.

Notably, Burton and Sondheim made significant changes when translating the score for screen. Some numbers were trimmed or cut (notably the omnipresent Ballad and much of the chorus work), in part to keep the film moving but also because Greek-chorus-style direct address is harder to realize cinematically. Musical numbers are shot and mixed as naturalistic, internal monologues, with cast performances—especially Depp’s—rendered in a whispery, confessional style suited for film but quite divergent from the stage’s operatic projection.

Musical Execution on Stage: Monumental, Operatic, and Ensemble-Driven

The Lansbury production uses the musical’s full epic sweep. The chorus and supporting cast join in massive, layered harmonies, often singing lines that overlap or contradict, creating mounting suspense and confusion. Songs as “Epiphany” and “A Little Priest” are performed with grand, theatrical energy, requiring actor-singer precision and unflagging stamina.

The orchestra’s texture is sometimes purposefully ugly—a soundscape designed to disturb, using harsh intervals, relentless ostinatos, and jarring percussion. But moments of lyricism (“Johanna,” “Not While I’m Around”) act as oases between storms, making the returns to horror all the more jarring. Live performance underscores the immediacy and danger; mistakes can bleed into the drama itself.

Lyrics and Libretto: The Macabre Made Verbal

The Lyrical Machinery: Wit, Irony, and Psychological Depth

Sondheim’s lyrics are a defining engine of horror in Sweeney Todd, blending macabre wordplay, puns on death and cannibalism, and psychological introspection. In both versions, the text is what allows us most directly into the malformed hearts and minds of the characters.

“A Little Priest,” a number pairing Sweeney and Mrs. Lovett as co-conspirators, exemplifies this tightrope-walk of gruesome humor. The lyrics pivot on occupational puns (“the priest tastes divine,” “the poet’s a bit tough—his verse is too long”), using wordplay both to amuse and to undercut the horror with disquieting amusement.

Deeper into Sweeney’s psyche are the lyrics for “Epiphany,” where revenge mutates into a cosmic principle—“We all deserve to die”—and horror fuses with existential despair. Elsewhere, Mrs. Lovett infuses cheerful practicality into her plans, deflating the horror even as she embodies it.

Performance Differences: Literalism vs. Irony

In the Lansbury musical, these lyrics are delivered with an awareness of the satirical, almost music-hall roots that underlie Sondheim’s approach. Lansbury’s Lovett sings with comic timing and breezy self-interest, making her horrific acts seem disturbingly mundane. Sweeney’s breakdowns are performed with operatic ferocity—a clarity of self-destruction that is almost cathartic.

In the Depp film, lyric interpretation is notably subtler and often more mournful. Many lines are whispered, internalized, or flattened, so that black humor yields to melancholy or sarcasm rather than laughter. Depp’s Sweeney rarely appears exhilarated by his own madness—instead he is numbed, tragic. The effect is more psychological horror, less gleeful villainy.

Key point: Whereas the stage version often “winks” at the audience through its lyrics, drawing attention to the theatricality and absurdity of the horror, the film roots the lyrics in lived experience—gruesome, miserable, and all but devoid of levity. Songs such as “By the Sea” become delusional fantasies rather than comic relief.

Chorus and Direct Address: Brechtian Devices vs. Cinematic Distance

The signature “Ballad of Sweeney Todd,” which bookends and weaves through the musical, is Sondheim’s Brechtian masterstroke. Its lyrics implore us not just to absorb, but to “attend the tale”—to examine our own capacity for horror. The musical uses the chorus to point a finger at audience complicity, to comment on proceedings, and to puncture the narrative with unsettling reminders that monsters are made, not born.

The film, by contrast, omits the chorus, except as instrumental underscoring. The effect is a flattened, more deterministic narrative: we are no longer reminded that we are watching a “tale.” Instead, we endure the horror alongside the characters, without relief from narrative distancing.

Gore, Special Effects, and Set Design

Film: Stylized, Relentless Gore

In keeping with Grand Guignol traditions (French horror theater famous for its stage effects), Burton’s Sweeney Todd foregrounds gore and violence. The throats are slit in close-up; blood sprays in arcs, pooling and pulsing with a disturbing, almost painterly flourish. The foley of slicing, thudding, and sizzling is graphic, making the horror not just visible but oppressive.

Special effects blend practical with digital: visual effects houses contributed hundreds of shots, from extending London’s skyline to rendering the mechanical actions of Todd’s barbershop chair. The violence is stylized enough to be unreal, lessening its nauseating impact but amplifying its shock. Death is ritualized, almost balletic.

Set design, under Oscar-winning designer Dante Ferretti, creates a city at once claustrophobic and mythic: interiors ooze with filth, decay, and malign beauty; exteriors are dreamlike in their grotesqueness. The interplay of set and special effects ensures the horror is everywhere, inescapable.

Stage: Suggestion, Stagecraft, and Choreography

Stage productions, including the Lansbury original, achieve horror less through spectacle than through choreography, imagination, and careful use of visible stage machinery. Blood is suggested—red scarves, flashes of light, sudden falls through trapdoors—leaving much to the audience’s imagination. The cumulative effect, aided by scale and the immediacy of live performance, is no less chilling.

Innovative set pieces, such as the revolving stage, mechanized chair, or use of scrim and silhouette, allow the rapid shifts between locations and emotional states that the narrative demands. Everything is constructed to serve the ratcheting-up of suspense: as bodies fall and disappear, the line between horror and farce blurs, forcing the audience to confront their reactions.

Directorial Influence: Burton versus Prince

Tim Burton: Gothic Fairytale Horror

Burton’s stamp is all over the film—from his use of star actors (Depp, Bonham Carter, Rickman) to the adoption of hallmarks from German Expressionism, classic horror, and his own filmography (Edward Scissorhands, Sleepy Hollow). His Sweeney Todd is a dead man walking, a lost soul animating a corpse. The empathy for monsters, a running motif in Burton’s work, transforms Todd into both villain and victim: blood is catharsis, violence is grief rendered visible.

Burton’s visual wit is darkly playful (the fantasy “By the Sea”), but he never lets the audience off the hook with easy laughter. Instead, he constructs a world so sealed, so airless and poisoned, that horror is the default atmospheric pressure.

Harold Prince: Epic Drama of Systems

Prince’s direction, in contrast, frames horror not just as a matter of individual torment, but as the inescapable outcome of history, technology, and class. The scale of the Uris Theatre’s epic steel-set reinforces the impotence of the individual: Todd is a small man dwarfed by the mechanisms—literal and figurative—of London. Prince’s direction ensures that we are always aware of the performance: the breaking of the fourth wall, the ambiguous tone, the sense that this is an awful joke being played by and on society. Horror, here, is the normalization of atrocity.

Horror Atmosphere: Final Synthesis

The horror of Sweeney Todd stems from more than murder or even revenge—it arises from the collapsing of boundaries between the comic, the tragic, and the mundane. Both the Johnny Depp film and Lansbury’s stage musical are masterpieces of horror not because they simply unsettle, but because they force us to examine the monsters lurking in human systems, psychology, and history.

- The film traps us in Sweeney’s crumbling mind and a necrotic city, using hyperreal violence, oppressive visuals, and deadpan singing to strip comfort from the viewer, leaving us with only despair and a grudging recognition of shared darkness.

- The stage musical envelopes us in grand design: the distance of satire, the comfort (and threat) of communal singing, the pleasure of sardonic wit. Horror is disarmed only to strike again—each pun makes the next razor stroke sharper.

Both versions are macabre, but their flavors differ: film is a bleak, blood-drenched dirge; stage is a complex, communal ritual—half-wake, half-warning.

Comparison Table: Johnny Depp Film vs. Angela Lansbury Stage Musical

| Feature | Johnny Depp Movie Version (2007, Burton) | Angela Lansbury Stage Musical Version (1979, Prince) |

|---|---|---|

| Director | Tim Burton | Harold Prince |

| Lead Actors | Johnny Depp (Todd), Helena Bonham Carter (Lovett) | Angela Lansbury (Lovett), Len Cariou/George Hearn (Todd) |

| Thematic Focus | Obsession, madness, psychological horror, gothic tragedy | Revenge, satire, class struggle, black comedy, social allegory |

| Lighting/Cinematography | Desaturated, high-contrast, stylized shadows, monochrome palette with vivid red blood | Expressionist theatrical lighting, chiaroscuro, highlights/darkness, industrial set |

| Ambient Sound | Dense, realistic foley, environmental sounds (machinery, rain), surround mix, silence as tension | Musical underscoring, live sound effects (whistles, creaks), chorus as atmosphere |

| Music/Orchestration | Cinematic, large orchestra (78), expanded Hollywood sound, subdued vocals for intimacy | Stage orchestra (27-30), operatic singing, full chorus, musical leitmotifs |

| Lyrics | Retained mostly intact but with trimmed/cut numbers; lyrics delivered more mournfully or internalized; little humor | Complete, witty, pun-laden, delivered with black humor; direct address in ballads |

| Chorus Function | Chorus and ballads cut, no direct audience address | Greek chorus, frequent audience address, Brechtian commentary |

| Violence/Gore | High, explicit, stylized “operatic” blood and violence, digital and practical effects | Implied/gestural, blood suggested via props or lighting, no explicit gore |

| Set/Scenic Design | CGI-enhanced, claustrophobic, expressionist London, detailed interiors | Large-scale industrial set, mechanized barber chair, trapdoor, revolving stage |

| Directorial Style | Psychological, tragic, cinematic Gothic horror, empathy for monsters | Epic, satirical, Brechtian, metatheatrical, social commentary |

| Overall Horror Tone | Gloomy, bleak, oppressive, focused on personal madness and vengeance | Playful yet sinister, communal, satirical, horror intertwined with humor |

| Reception | Critical acclaim, praised for style and performances, some criticism for lack of humor, strong cult following | Widely regarded as a masterpiece, Tony Award-winner, praised for innovation and blend of horror/comedy |

| Copyright/Use | Film and adaptation copyright held by film studio and Sondheim estate; cannot be used in entirety but reviewing and comparison fall under fair use and public commentary | Musical copyright for book, lyrics, and score; previous material (String of Pearls, Bond play) is public domain; analysis and commentary safe under fair use |

| Commercial Safe Use | Reviews, comparisons, analyses, and brief quotations are covered by fair use. The original “String of Pearls” story and Penny Dreadful-era characters (i.e., Sweeney, Lovett) are public domain. | Same: character archetypes and 19th-century plot public domain; Sondheim’s music/lyrics not for unlicensed commercial reuse. Analytic writing and criticism is safe. |

Elaboration:

This table encapsulates both factual divergences (direction, cast, staging) and the deeper aesthetic/philosophic angles: the Johnny Depp/Tim Burton film engraves horror through cinematic realism and psychological decay, while the Lansbury/Prince musical enlists the audience in a ritual of horror and laughter, constantly reminding us that the machinery of society—and theater itself—both devours and delights.

Audience and Critical Reception

The Johnny Depp film was lauded by critics for its visual boldness, musical fidelity, and potent performances, particularly Depp’s haunted, brooding turn. Some critics lamented the loss of stage humor and the flattening of Sondheim’s layered lyrics, but most recognized it as an audacious, effective horror musical that brought Grand Guignol to a new generation.

The Lansbury musical is universally regarded as a landmark in musical theater, winning multiple Tony Awards and achieving legendary status for both Sondheim’s craftsmanship and the fusion of operatic, horror, and comedic traditions. Critics and audience members alike cite its ability to both scare and amuse, as well as its daring embrace of darkness without losing emotional depth.

Both have spawned revivals, critical studies, and a devoted fanbase, attesting to the enduring power of Sweeney Todd’s horror—in whatever form it slices.

Which Version Chills More Deeply?

From the shriek of the steam whistle to the shrill of a razor, from sardonic laughter to gory catharsis, Sweeney Todd endures as a masterpiece of horror in both musical and filmic guises. Lansbury’s stage is a raucous, Brechtian feast of fear and fun; Burton’s film is an elegiac tomb, muraled in blood and soot. Both dissect the machinery of revenge, power, and loss, and both ask the audience—through comedy or catharsis—to “attend the tale.” Their differences are as essential to the experience as their similarities: two sides of the razor, two paths through the pit, each wielding horror with exquisite style.

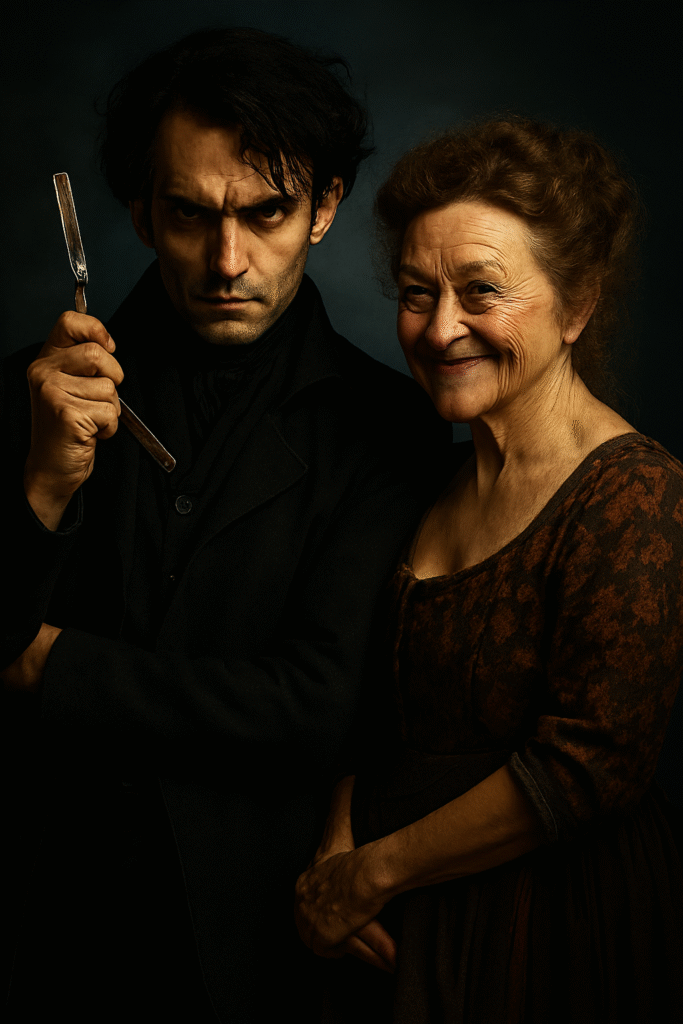

Become the Demon Barber Himself

Step into the shadows of Fleet Street with this complete Sweeney Todd cosplay outfit. Perfect for Halloween haunts, theatrical flair, or eerie ensemble shoots. Every stitch whispers vengeance.

Shop the CostumeWickedly Wearable

Whether you’re slicing through spreadsheets or serving up sarcasm, these shirts let you rep the twisted charm of Fleet Street. One for the barber, one for the baker—wear them solo or as a sinister duo.

Sweeney Todd’s Barber Shop TeeMrs. Lovett’s Pie Shop Tee

Blood, Music, and Genius

Unmask the brilliance behind the blades. Rick Pender’s deep dive into Sondheim’s masterpiece reveals the haunting harmonies and theatrical alchemy that made Sweeney Todd a legend.

Read the BookHear the Horror, See the Sin

Experience the tale in two unforgettable forms: the chilling original Broadway cast recording and Tim Burton’s gothic cinematic retelling. Perfect for setting the mood or deepening your lore.

Original Broadway HighlightsTim Burton’s Sweeney Todd DVD

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.