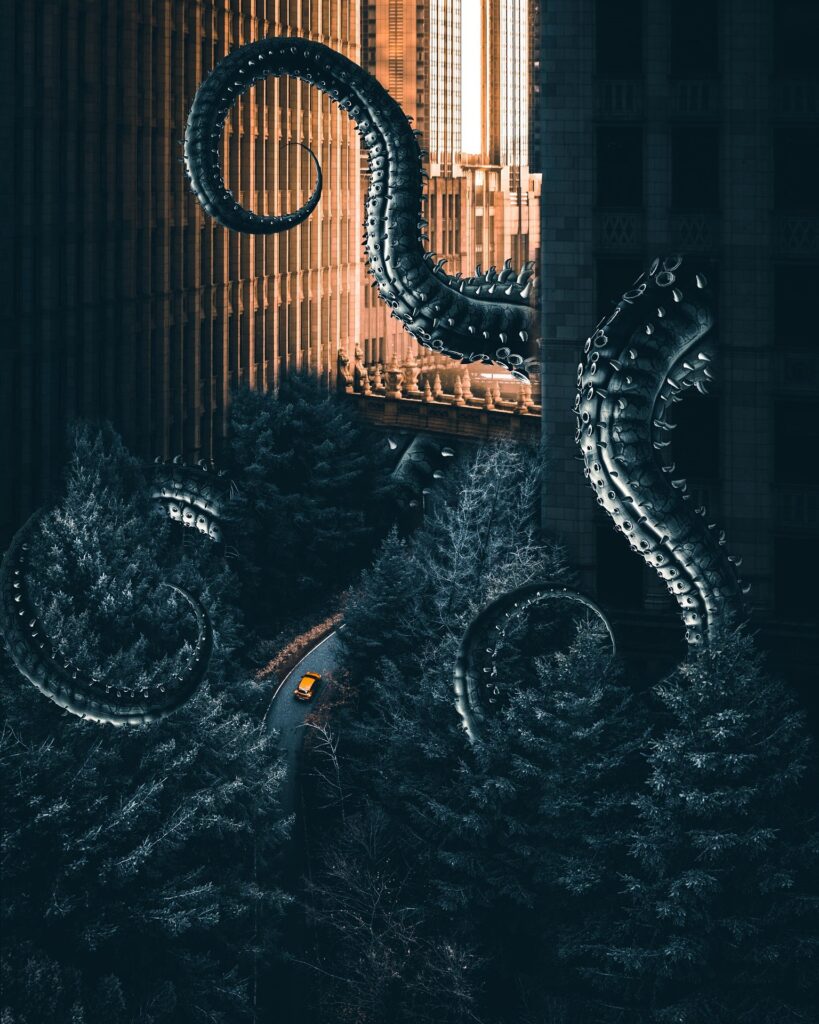

I must admit that when I first encountered octopi, my experience was one of reading H.P. Lovecraft and delving into the Cthulu mythos as opposed to the oceanic creature, so I sincerely believed they looked a bit like this:

Luckily, they do not. Yet, for me in my active imaginative thinking, I got interested in them as a vague and general kind of concept. Imagine my joy, as this problematic autistic person with a budding special interest in octopi and a very strong interest in Lovecraft, when I learned that the Giant Pacific Octopus at a Seattle Aquarium was unaliving ALL of their dogfish sharks. The workers of the aquarium would go home and there would have been sharks in the tank and when they came back in the morning, they were missing. Finally, they set up a camera and caught footage of the octopus attacking, killing and eating the sharks, which led the aquarium to place the remainder of the dog sharks into a different tank in the ultimate show of time out.

So, what began as a Lovecraftian curiosity quickly spiraled into a full-blown obsession with one of nature’s most alien minds- plural, because an octopus has nine of them.

Besides having no bones, nine brains and three hearts, what makes octopi so incredible? Let’s dive in and find out!

Aliens of the Deep

Okay, admittedly octopi are not literal aliens. With a lineage that goes back over 330 million years, DNA that is wildly complex and an evolutionary progression that is bizarre at best, yet also incredibly confusing and mind-blowing, some scientists have jokingly started calling the cephalopods “aliens of the deep”.

Add to that the ability to change color, texture, and even masquerade as a completely different animal, not to mention the ability to regenerate entire limbs, it makes sense that octopi may be seen as aliens. After all, a certain Gallifreyan Doctor had a spaceship that could do that, they had two hearts, and they could regenerate their entire body as well.

And if you’re still thinking of octopi as dinner rather than deep-sea enigmas… You might want to reconsider. There have been documented cases where severed octopus limbs—completely detached from the body—still respond to stimuli. They twitch. They grasp. They move. Imagine sitting down to a plate of sashimi and having your food reach for your fork. Suddenly, the alien metaphor doesn’t feel so metaphorical. While you may think that an octopus couldn’t possibly grab a fork, it is worth mentioning that Scientists have watched them unscrew jars from the inside, pry open childproof bottles, and solve puzzles with unnerving finesse. If they can open a jar, they most certainly can grasp a fork.

Otto the Prankster

What else can these amazing creatures do besides be incredibly creepy and unnerving? Well, for that, we pivot and look to Otto. Otto was a common octopus (octopus vulgaris) who lived in the Sea Star Aquarium in Coburg, Germany, and actually was a little bit vulgar. He would juggle hermit crabs out of boredom like a circus performer, rearrange his habitat on a whim, and hurl rocks at the glass just to stir things up. Most famously, he used perfectly aimed jets of water to short-circuit the spotlighting system, plunging the aquarium into darkness and baffling the staff until they caught him in the act. Turns out, he was just being playful.

Emotional Intelligence of the Octopus

Playfulness is a trait of emotional intelligence, and octopi have shown playfulness in spades, not just with Otto, but even in the wild. In tide pools and reef environments, octopi have been seen picking up shells, rocks, and even discarded bottle caps, then tossing or carrying them around without any clear survival purpose. It’s not hunting. It’s not defense. It’s just… fiddling. Some wild octopi have been observed directing water jets at floating objects, like bottles or shells, repeatedly and with apparent aim. It’s eerily similar to how captive octopi play with water streams in tanks. Though typically solitary, isolated octopi have been seen shoaling with fish—swimming alongside them in coordinated movements. It’s not predatory, and it doesn’t seem territorial. It’s more like social curiosity. In the wild, octopi often explore crevices, coral structures, and even scuba gear with what looks like playful curiosity. They’ll reach out, touch, retract, and repeat—sometimes for extended periods, as if testing boundaries or just entertaining themselves. Play is often considered a marker of higher intelligence and emotional complexity. The fact that octopi do this without training or reward in the wild suggests that their minds are wired for more than just survival—they seek stimulation, novelty, and maybe even fun.

Octopi don’t just change color to blend in—they also do it to express internal states. Researchers have observed octopi shifting hues in response to stress, excitement, or even sleep cycles. One study documented an octopus changing color while dreaming, suggesting a rich inner life that’s still largely mysterious.

Some octopi recognize individual human handlers and respond differently to them. They’ve shown signs of liking or disliking certain people—approaching some with curiosity, avoiding others entirely. That’s not just instinct; it hints at memory, preference, and maybe even emotional nuance.

A 2021 study provided strong evidence that octopi not only feel physical pain but also experience emotional suffering in response to it. They showed spontaneous behaviors and neural activity consistent with negative emotional states—something previously thought impossible for invertebrates.

While traditionally seen as loners, some species have been observed engaging in social behaviors—gesturing, changing color in response to others, and even living communally under certain conditions. It’s rudimentary, but it suggests a capacity for interaction that goes beyond survival.

The Intelligence of Nine Brains

Octopi have around 500 million neurons, which is staggering for an invertebrate. But here’s the twist: over two-thirds of those neurons are in their arms, not their central brain. Their body is built with one central brain in their body and one brain in each of their arms.That means each arm can sense and react to stimuli independently, explore objects without needing permission from the “main” brain, and even make decisions on its own, like whether to grasp, taste, or retreat. It’s like having eight semi-autonomous limbs that think for themselves. Imagine if your fingers could decide what to touch without you knowing—it’s alien, but it’s real.

Yet, the intelligence is not standardized throughout the different species. Each individual octopus, much like humans, have their own personalities, quirks, strategies and moods. The evidence of this is seen in instances such as the Giant Pacific octopus in Seattle who violently turned the tables on its natural predators, or Otto being mischevious and causing the power to go out in the entire facility with one well placed water spray.

Marine scientists have noted that in labs, octopi have solved complex puzzles, like opening jars or navigating mazes, escaped enclosures, sometimes by memorizing guard routines or manipulating latches, shown preferences for certain humans, approaching some and avoiding others and displayed unique behavioral patterns, suggesting individual personalities—some bold, some shy, some downright mischievous. All of this speaks to the cognition and problem-solving skills, as well as the emotional intelligence of the octopi in our world.

Blue Blood = More Hearts

Octopi have three hearts because their blood is blue, copper-based, and not particularly efficient at transporting oxygen. They have two branchial hearts pump blood through the gills, where it picks up oxygen. Each heart serves one gill and one systemic heart then circulates that oxygen-rich blood throughout the rest of the body. This setup compensates for their hemocyanin-based blood, which is less efficient than our iron-rich hemoglobin. It’s a clever workaround for surviving in cold, low-oxygen environments—like the deep sea or chilly coastal waters.

When an octopus swims, its systemic heart actually stops beating. That’s why they prefer crawling—swimming exhausts them. Imagine your heart taking a break every time you jog. It’s bizarre, but it works for them. So in essence, three hearts aren’t overkill—they’re a necessity for a creature with blue blood, high metabolic demands and a boneless, shape-shifting body that needs constant oxygen flow.

The Chameleon Circuit

Octopi don’t just have blue blood—they practically live in a sci-fi script. Their copper-based hemocyanin gives them that eerie, alien-blue hue, a biochemical quirk that helps them survive in cold, low-oxygen environments. But the weirdness doesn’t stop there.

Let’s talk about a different kind of blue: the blue box.

In Doctor Who, the Chameleon Circuit was a device inside the Doctor’s TARDIS (Time and Relative Dimension in Space)—a time-traveling spaceship designed to blend into its surroundings. But when the circuit broke, the TARDIS got stuck in the form of a blue 1960s British police box. Iconic, yes. But also a glitch in its camouflage.

Octopi, on the other hand, have a Chameleon Circuit that works. They shift colors, textures, and even mimic other species. One moment they’re coral, the next they’re a flounder. Their skin is a living canvas, controlled by thousands of chromatophores that respond to light, emotion, and intent.

Where the Doctor’s ship failed to blend in, the octopus thrives in disguise. It’s not just camouflage—it’s transformation. It’s survival through illusion. It’s nature’s version of a cloaking device, and it’s functional.

Octopi are masters of disguise thanks to a complex system of chromatophores, iridophores, and leucophores embedded in their skin: Chromatophores are tiny pigment sacs surrounded by muscle fibers. When the muscles contract, the sacs expand, revealing color. When they relax, the color fades. These pigments include reds, browns, and yellows. Iridophores reflect light to create shimmering blues, greens, and silvers—like underwater glitter. Leucophores scatter ambient light, helping the octopus match the brightness of its surroundings.

But it’s not just color. Octopi also change texture using papillae, small muscle-controlled bumps that can make their skin look like coral, rock, or sand. Combine that with their boneless bodies and you’ve got a creature that can vanish into almost any environment.

The Mimic Octopus (Thaumoctopus mimicus), discovered in Indonesia in 1998. It doesn’t just blend in—it impersonates. It can mimic lionfish by spreading its arms to resemble venomous spines. It impersonates sea snakes, flatfish, jellyfish, and even mantis shrimp, adjusting its movement, posture, and color to match. It chooses which creature to mimic based on the predator nearby—like a shapeshifter with a strategy. This octopus doesn’t just hide—it performs. It’s the closest thing we have to a real-life changeling.

The Myth, The Legend, The Elder God

The Myth: The Kraken

The Kraken is the primordial terror of the sea, a creature born from Norse mythology and sailor superstition. Said to dwell off the coasts of Norway and Greenland, this colossal, tentacled beast was believed to rise from the depths to drag entire ships into the abyss. Though likely inspired by sightings of giant squids, the Kraken transcended biology to become a symbol of chaos, unpredictability, and the vast, unknowable power of the ocean. It represents the fear of what lurks beneath—the monstrous unknown that defies human control. In mythic terms, the Kraken is nature’s wrath incarnate, a reminder that the sea does not answer to us.

The Legend: Hokusai’s Octopus

In 1814, Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai created a woodblock print that would ripple through centuries of art and interpretation: The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife. In it, an ama diver is entwined with two octopi in a surreal, erotic embrace. While often viewed through the lens of Edo-period eroticism, the image also carries deeper symbolic weight. It blurs the boundaries between human and animal, desire and danger, pleasure and power. Some interpret it as a reversal of dominance—a moment where the octopus enacts revenge or claims agency. The legend here isn’t just the image itself, but the cultural shockwave it created. It’s a tale of entanglement, transformation, and the merging of marine mystery with human vulnerability.

The Elder God: Cthulhu

Then there is Cthulhu, the tentacled titan of cosmic horror introduced by H.P. Lovecraft in The Call of Cthulhu (1928). Described as part octopus, part dragon, and part humanoid, Cthulhu sleeps in the sunken city of R’lyeh, dreaming until the stars align and he rises again. The infamous chant—“Ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn”—translates to “In his house at R’lyeh, dead Cthulhu waits dreaming.” Unlike traditional monsters, Cthulhu isn’t evil. He’s indifferent. He represents the terrifying idea that the universe is vast, ancient, and unconcerned with human existence. Cthulhu is the embodiment of existential dread, a god whose very presence fractures sanity and whose motives are beyond comprehension.

Why Are Octopi Important, Anyway?

Octopi aren’t just fascinating—they’re foundational.

Ecological Architects

Octopi are both predator and prey, playing a crucial role in maintaining marine balance. They regulate populations of crustaceans, mollusks, and small fish, preventing any one species from overrunning the ecosystem. Think of them as the ocean’s population control officers—stealthy, strategic, and essential.

Evolutionary Outliers

Their intelligence is a biological anomaly. With nine brains, three hearts, and a decentralized nervous system, octopi challenge our understanding of cognition. Studying them helps scientists rethink what intelligence is, and how it might evolve in radically different forms.

Scientific Inspiration

Octopus camouflage has inspired breakthroughs in materials science, military tech, and robotics. Their ability to change color and texture instantly is being studied to develop adaptive surfaces and soft-bodied machines.

Emotional & Ethical Awakening

octopi feel pain, show preferences, and exhibit playfulness. Recognizing their emotional intelligence forces us to reconsider how we treat non-human minds. Should we eat creatures that solve puzzles and mourn? Should we keep them in tanks when they sabotage the lighting out of boredom?

Mythic & Cultural Resonance

From Lovecraft’s Cthulhu to Japanese folklore, octopi have haunted our stories for centuries. They symbolize mystery, transformation, and the unknown. They’re not just animals—they’re archetypes.

So why are octopi important? Because they’re not just part of the ocean. They’re part of the conversation—about intelligence, emotion, ethics, and the alien beauty of life on Earth. What started, for me, as a vague reference from H.P. Lovecraft about a giant octopus god exploded into understanding the aliens of the deep, and realizing that we’re not as different as most would think. If creatures who have no bones or social structures can be this intelligent, adaptive and quirky, how amazing would it be for scientists to learn exactly how similar humans are- not just to octopi, but to the entire world around us?

So what do you do after falling down the tentacled rabbit hole? You start collecting. Whether it’s books on cephalopod intelligence, octopus-themed decor, or tools for exploring the ocean’s mysteries yourself, there’s a whole world of octo-curiosities waiting to be discovered. Below are a few handpicked finds that celebrate the brilliance, beauty, and bizarre charm of the octopus—from science to symbolism, and everything in between.

🛍️ A Note on Links

Some of the links below are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission—at no extra cost to you—if you choose to make a purchase. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. I only share items I genuinely believe support reflection, healing, or creative engagement.

Your support helps sustain this blog and the advocacy work behind it. Thank you for being here.

Qiuenisray Irregular Octopus Puzzle

This isn’t just a puzzle—it’s a tactile tribute to tentacled elegance. With 100+ uniquely shaped wooden pieces, this compact 11.2″ x 11.2″ jigsaw features a vibrant octopus in swirling blues and purples, rendered in a stained-glass style. The irregular cuts and animal-shaped pieces make it feel alive, like assembling a creature that thinks in fractals. Whether you’re decompressing, meditating, or just indulging your inner cryptozoologist, this puzzle is a satisfying dive into pattern, color, and complexity. Perfect for neurodivergent minds that thrive on immersive, nonlinear play.

Light-Up Taxidermy Octopus

A real octopus specimen preserved in resin, displayed on a color-changing LED base. Equal parts science and spectacle—ideal for collectors, educators, or anyone who wants a glowing reminder of the deep.

Secrets of the Octopus by Sy Montgomery

A beautifully illustrated dive into octopus intelligence, emotion, and behavior—written by the “octopus whisperer” herself. This book is a companion to the National Geographic series and features vivid photography and compassionate storytelling.

TYSO Octopus Necklace

Crafted from 925 sterling silver and moonstone, this necklace blends elegance with symbolism. The octopus design evokes transformation, mystery, and fluidity—perfect for sea lovers and shapeshifters alike.

Cool Blue Octopus TShirt

A playful, eye-catching tee with sustainability credentials (OEKO-TEX certified). Great for casual wear or making a statement at your next marine biology meetup.

Eco-Friendly Octopus Plushie

Soft, sustainable, and ethically made—this plush from Wild Republic’s Pocketkins Eco line is crafted from recycled materials and meets global safety standards. A cuddly tribute to conservation.