Parsing the Line Between Historical Fact and Broadway Brilliance

SIX, the British musical comedy phenomenon by Toby Marlow and Lucy Moss, has rapidly evolved from its 2017 Edinburgh Fringe debut into a global sensation, invigorating the canon of musical theatre with its audacious “historemix” of 16th-century queens and 21st-century pop icons. At the heart of this musical lies a bold creative conceit: Henry VIII’s six wives, reimagined as a glittering girl group, reclaim their narratives through a competitive pop concert, each vying to determine who suffered most at the hands of the infamous king. The women’s stories are broadcast through infectious songs, playful banter, and a finale that subverts the idea of competition, ultimately asserting each queen’s individuality and agency.

If you’re curious about the real histories behind SIX, I highly recommend The Six Wives of Henry VIII by Antonia Fraser and, for fans who want to sing along or relive the show at home, the official SIX soundtrack featuring Andrea Macaset as Anne Boleyn —both are affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission if you purchase at no extra cost to you.

Yet, with this radical approach comes a fascinating interplay between historical accuracy, dramatic license, and modern sensibility. While SIX is peppered with true-to-life details—from key biographical points to personal triumphs and tragedies—it unapologetically prioritizes empowerment, humor, and emotional truth over strict adherence to fact. This post unpacks the real lives of Henry’s queens, evaluates how each is portrayed in SIX, and examines the creative liberties that transform “history” into dazzling, character-driven musical theatre.

As a special treat for fans of Andrea Macasaet (and honestly, what theatergoer isn’t?), this exploration will spotlight her vivacious, scene-stealing performance as Anne Boleyn, particularly during the iconic “Don’t Lose Your Head” – without giving away any lyrics, but certainly with a wink of delight at a particularly memorable moment.

Concept and Creative Team: From History Textbooks to Backstage Passes

The creative genesis of SIX is itself a revolution in theatre-making. Conceived by Toby Marlow (then at Cambridge University) during a poetry lecture, and brought to fruition with his classmate Lucy Moss, the show was envisioned not out of a particular love for Tudor history, but from a passion for reclaiming women’s voices in musical theatre—and providing “funny and hilarious” stage time for female performers who so often played secondary roles.

In developing SIX, Marlow and Moss delved into academic sources like Antonia Fraser’s The Six Wives of Henry VIII and documentaries led by historians such as Lucy Worsley, ensuring a solid factual foundation. But they also intentionally modelled each queen on pop music icons—think Beyoncé, Avril Lavigne, Adele, Nicki Minaj, Britney Spears, and Alicia Keys—to give them distinct 21st-century personalities and musical flavors. Gabriella Slade’s ingenious costuming blends Tudor silhouettes with superstar chic, further blurring the lines between “then” and “now”.

The result is a show that is both dazzlingly theatrical and deeply resonant, achieving what Moss describes as “reframing the way that women have been perceived in history and telling their side of the story”.

Catherine of Aragon: Queen, Regent, and Trailblazer

Historical Background

Catherine of Aragon (1485–1536) was a formidable figure whose impact far exceeded that of a mere royal wife. The Spanish princess was initially married to Henry’s brother, Arthur. Upon Arthur’s death, she spent years in diplomatic limbo before finally wedding Henry VIII, forging an alliance vital for Tudor legitimacy in Europe. Catherine was a passionate advocate for her daughter, Mary; a regent who orchestrated policy while Henry campaigned abroad (even presiding over a military victory against Scotland); and the first female ambassador in European history.

Her legacy includes an uncompromising refusal to accept her marriage’s annulment—a stand that would catalyze England’s split from the Catholic Church. Even after her demotion to Dowager Princess, Catherine commanded the English people’s respect and sympathy.

Portrayal in SIX

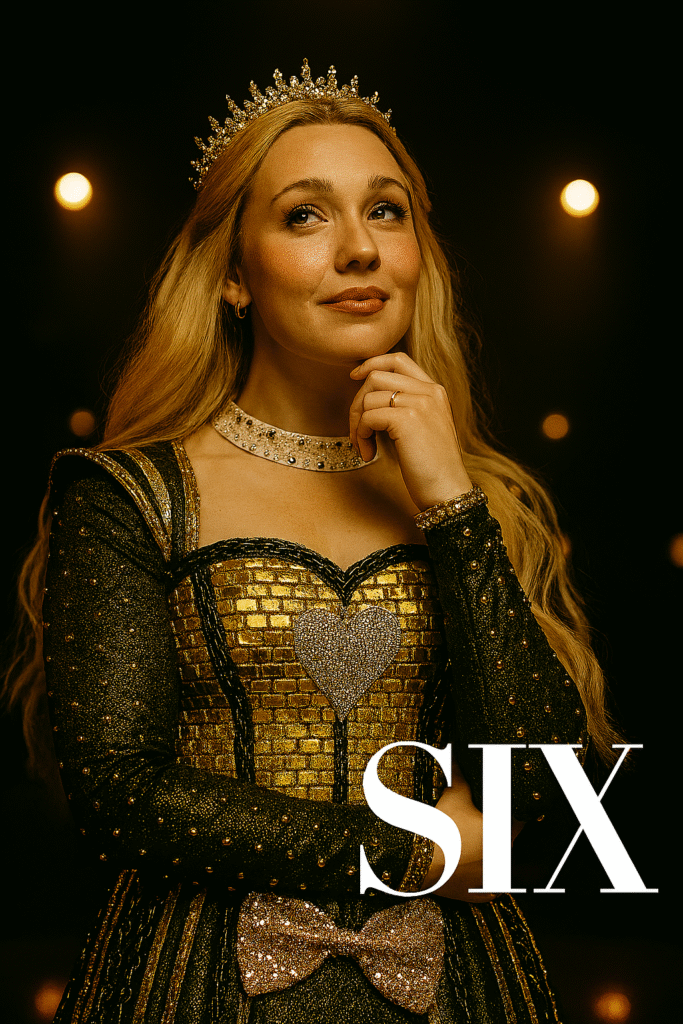

SIX’s Catherine of Aragon, typically styled in regal gold with an undeniable Beyoncé aura, enters the show as the clear group “lead.” Her solo “No Way” radiates proud defiance, capturing her resistance to Henry’s attempts to annul their marriage and remove her from the throne. The musical highlights her loyalty, the injustice of her fate, and her refusal to be silent—a fitting interpretation, if somewhat compressed.

Creative Liberties and Analysis

SIX—much like the history books—focuses Catherine’s story through the lens of her childlessness and the subsequent “Great Matter,” i.e., Henry’s quest for annulment. Some of her most remarkable achievements—her governance as regent, her advocacy for education, and singular diplomatic efforts—are alluded to obliquely, if at all. Instead, “No Way” re-centers her as a figure of proud female resistance against patriarchal machinations, reflecting both historical reality and the feminist resonance central to the show.

The pop-diva presentation, modeled after Beyoncé and Jennifer Hudson, condenses Catherine’s persona into a symbol of strength and assertiveness, sometimes at the expense of her more nuanced, devout, and intellectual sides. However, as critics and historians often note, such bold distillations are necessary for theatrical impact.

Anne Boleyn: Legend, Scandal, and a New Kind of Queen

Historical Background

Anne Boleyn (c. 1501/1507–1536) was arguably Henry’s most infamous wife—a woman of wit, sophistication, and political savvy. Educated at the courts of Margaret of Austria and France’s Mary Tudor and Queen Claude, Anne brought a cosmopolitan influence and “French manners” to the English court. She refused Henry’s advances unless he married her, which led directly to the English Reformation; their union resulted in the birth of the future Elizabeth I.

Despite—or perhaps because of—her power, Anne was undermined by court factions, accused (almost certainly falsely) of adultery, incest, and treason, and beheaded after only three years as queen.

Portrayal in SIX

Anne Boleyn in SIX is irreverent, self-aware, and a quintessential antiheroine—a “party girl” with a mischievous streak and a penchant for side-eye, humor, and campy rebellion. Her anthem “Don’t Lose Your Head” is a riotous, pop-punk-inspired romp (think Avril Lavigne and Lily Allen), lampooning both her own notoriety and the absurdity of the circumstances that led to her downfall.

Andrea Macasaet’s Performance: A Fan’s Perspective

Let’s just take a moment for Andrea Macasaet. Her “fresh & spicy” Anne – equal parts “sorry-not-sorry” and endlessly charismatic – crackled on the Broadway stage, earning praise for finding new nuances each night in the durable sass-meets-sincerity of Boleyn’s arc. She embodied Anne’s contradictions: bold yet vulnerable, self-effacing yet grounded in secret wounds. Macasaet’s comedic timing in “Don’t Lose Your Head”—especially the bit involving the hand gesture that shouldn’t work but totally does—delivered a moment of pure theater magic. If the creative team asked Anne Boleyn to wink at centuries of slander and turn it on its head, Macasaet delivered, every time. You can hear Andrea Macaset completely freak out during “Don’t Lose Your Head” here.

Creative Liberties and Analysis

Here, SIX’s greatest strength coincides with its greatest departure from the historical record. Anne in history was intensely political, intellectually engaged, and arguably not as flighty nor as “Instagram-captions-before-Instagram” as portrayed. She most likely did not “steal the crown” nor pursue Henry; if anything, he pursued her relentlessly, often with Anne seeking only what autonomy she could manage in a perilous court.

However, the musical’s deliberate comedic pivot subverts her “scheming temptress” reputation, instead presenting her as someone swept along by events she can’t control. The “sixth finger” joke, the green sleeves (referencing the legendary but probably apocryphal connection to the song “Greensleeves”), and the “B” necklace, all play on her pop-cultural afterlife as much as her life.

Despite the stereotypes, SIX’s Anne is astute: her self-conscious irreverence is an armor, and the show’s outrageous humor becomes a vehicle for both feminist catharsis and historical reevaluation.

Jane Seymour: The Good Wife Reconsidered

Historical Background

Jane Seymour (c. 1508–1537), Henry’s third queen, is often written off as the docile, obedient contrast to Catherine and Anne. Daughter of country gentry, Jane served as lady-in-waiting to both of her predecessors and, somewhat questionably, caught Henry’s attention while Anne still lived. Jane’s triumph was giving birth to Edward VI, the longed-for male heir, but she died of postpartum complications less than two weeks later. Her passing left Henry devastated; she is the only wife buried beside him.

Portrayal in SIX

In “Heart of Stone,” Jane’s ballad, the role channels Adele and Sia: emotional, plaintive, and earnest. Here, Jane claims both pride and pain in her role as Henry’s “true love” and the mother of a son, suggesting quiet strength beneath outward compliance. The show gives her space to grieve, reminding the audience that unwavering love can itself carry tragedy.

Creative Liberties and Analysis

SIX amplifies Jane’s traditional reputation as the loving, loyal wife, but adds an undertone: her love was conditional, her elevation deeply dependent on her ability to provide a male heir—a stark reminder of the gendered pressures of Tudor royalty. Yet, historical sources suggest Jane did have a mind of her own, advocating for the reconciliation of Henry with his daughters, and showing shrewdness in negotiating her new position. The musical’s portrayal largely mirrors her mythic status, though, rather than probing the (limited) evidence of her personality.

Still, as a moment of stillness in the show’s riotous energy, “Heart of Stone” accomplishes its aim, cementing Jane as both a product and victim of her times.

Anne of Cleves: Portraits, Power, and Post-Marital Bliss

Historical Background

Anne of Cleves (1515–1557) was Henry’s German “Flanders Mare” (a nickname unfairly posthumous), whose six-month marriage ended in annulment on grounds of non-consummation. The alliance was forged to patch up Protestant relations on the Continent, but Henry—having relied on Hans Holbein’s (apparently too-flattering) portrait—was publicly disappointed by Anne’s appearance and “lack of sophistication”. He swiftly arranged an annulment, but Anne’s pragmatic acceptance won her a generous settlement, estates, and favored status as “the King’s Beloved Sister”; she remained close to the royal household and outlived all rivals.

Portrayal in SIX

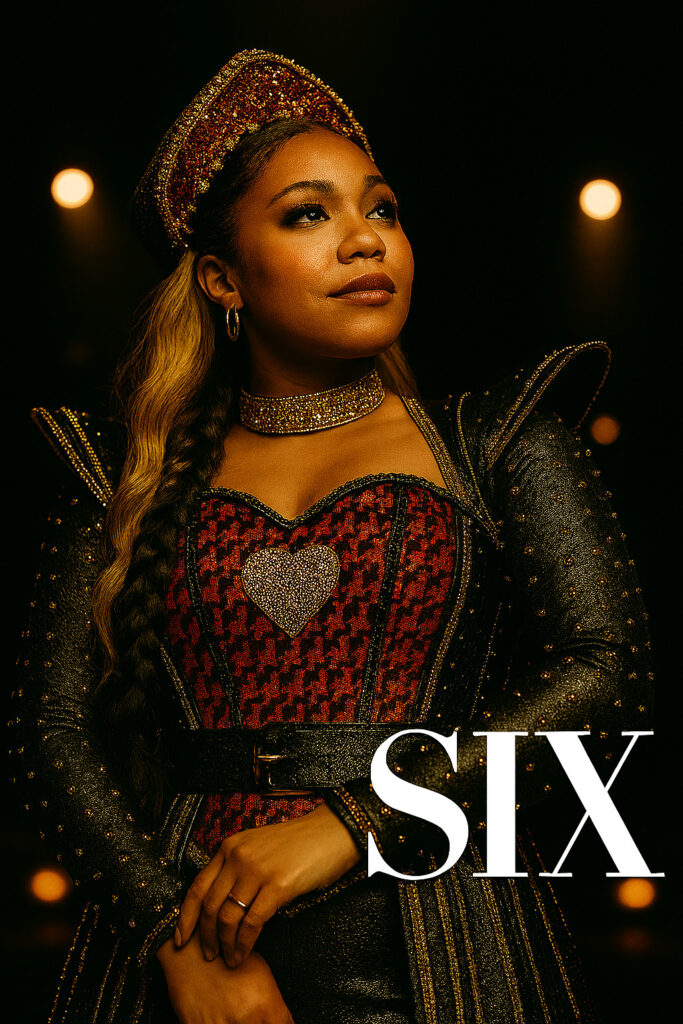

“Get Down,” the number dedicated to Anne, recasts her as a Nicki Minaj or Rihanna-style diva, gleefully flaunting her independence and the material perks of divorce. She is the “Queen of the Castle,” living in comfort, throwing shade with aplomb, and mocking the tragic narratives of the other wives. Her song, and persona, turn an oft-forgotten queen into the surprise “winner” of the show’s early narrative.

Creative Liberties and Analysis

SIX leans into the legend that Anne was dismissed due to a lack of beauty, which, as historians repeatedly emphasize, is suspect—contemporary accounts often praise Anne’s appearance and highlight Henry’s own capriciousness or possible impotence. The musical’s Anne is bold, brash, and delightfully unserious, bearing little resemblance to the genuinely gentle, pious, and somewhat awkward historical Anne; her musical character caricatures the idea of the “grateful divorcee.” Yet, the underlying truth remains: Anne did, by all accounts, enjoy one of the better post-marital arrangements and, in not contesting the annulment, survived the Tudor court unscathed.

Her solo, ultimately, is an affectionate parody of girl-boss empowerment, but its confidence gives overdue limelight to a woman sometimes erased from popular memory.

Katherine Howard: The High Cost of Being Desired

Historical Background

Katherine Howard (c. 1523–1542), Henry’s teenage bride, was swept from a chaotic, unsupervised childhood with the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk into the heart of the Tudor court. Bright, charming, pretty, and possibly as young as 17 at her marriage, she caught the king’s eye while serving Anne of Cleves. Her prior sexual relationships were later weaponized against her; she was beheaded for adultery less than two years into her queenship.

Historians now increasingly interpret Katherine as a victim of grooming and abuse, challenging the “promiscuous wanton” stereotype long perpetuated in popular culture.

Portrayal in SIX

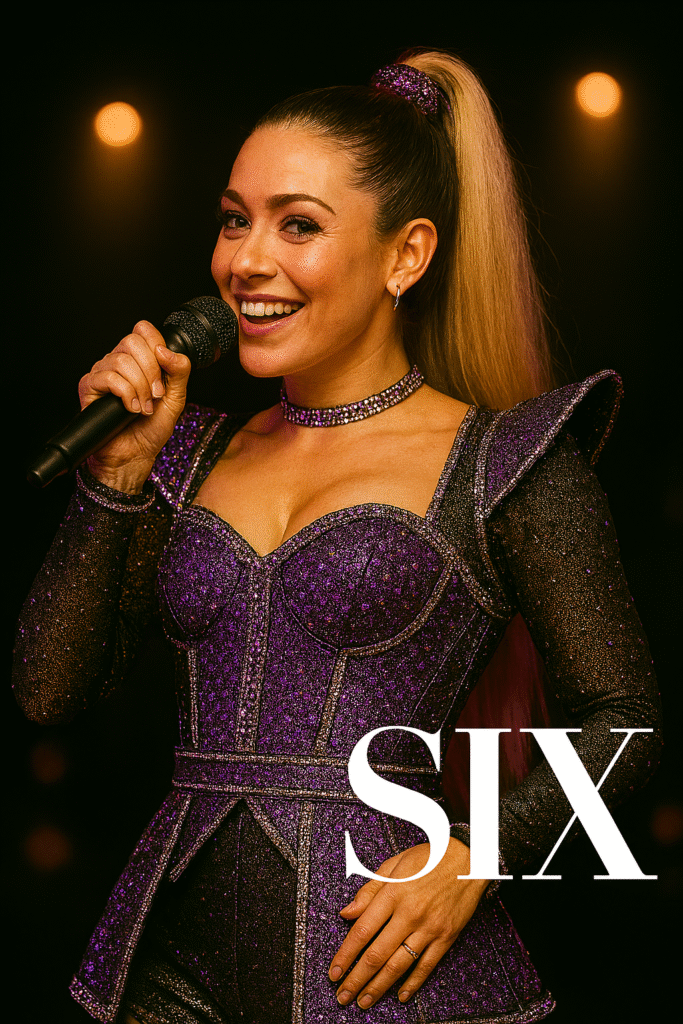

SIX achieves something remarkable with Katherine Howard’s song “All You Wanna Do.” Initially bubblegum pop in the mode of Ariana Grande or Britney Spears, the song’s tone darkens as Catherine cycles through a litany of predatory men and broken trust. The cheeky choruses become more desperate, the smile more brittle, until the façade finally shatters.

This modern, MeToo-inflected portrayal is both timely and devastating, giving Katherine her due as a tragic casualty of courtly power plays and sexism.

Creative Liberties and Analysis

The song’s ingenious structure subverts expectations: what starts as a celebration of sexual agency is revealed as a record of exploitation. SIX streamlines complex relationships (e.g., Henry Mannox and Francis Dereham) and leans into the dramatic, but is commendably sensitive in reinterpreting Katherine as less a “juvenile delinquent” and more the product of a world that only valued her beauty. The decision to have her costume be the most revealing is both a nod to history and a commentary on the ways she was objectified and abused.

SIX’s handling of Katherine Howard is a much-lauded example of dramatizing trauma without wallowing in tragedy, using pop to draw audiences in and then pull the rug away—leaving many in tears by song’s end.

Catherine Parr: Survival, Scholarship, and Legacy Beyond the Throne

Historical Background

Catherine Parr (1512–1548) was both more and less than “the survivor.” Four times married, she was an accomplished writer (the first English queen to publish under her own name), regent while Henry campaigned in France, a stepmother to three royal children, and an advocate for Protestant reforms.

After Henry’s death, Parr finally married for love—Thomas Seymour—yet died of postpartum complications only a year later, capping a life as volatile as it was groundbreaking.

Portrayal in SIX

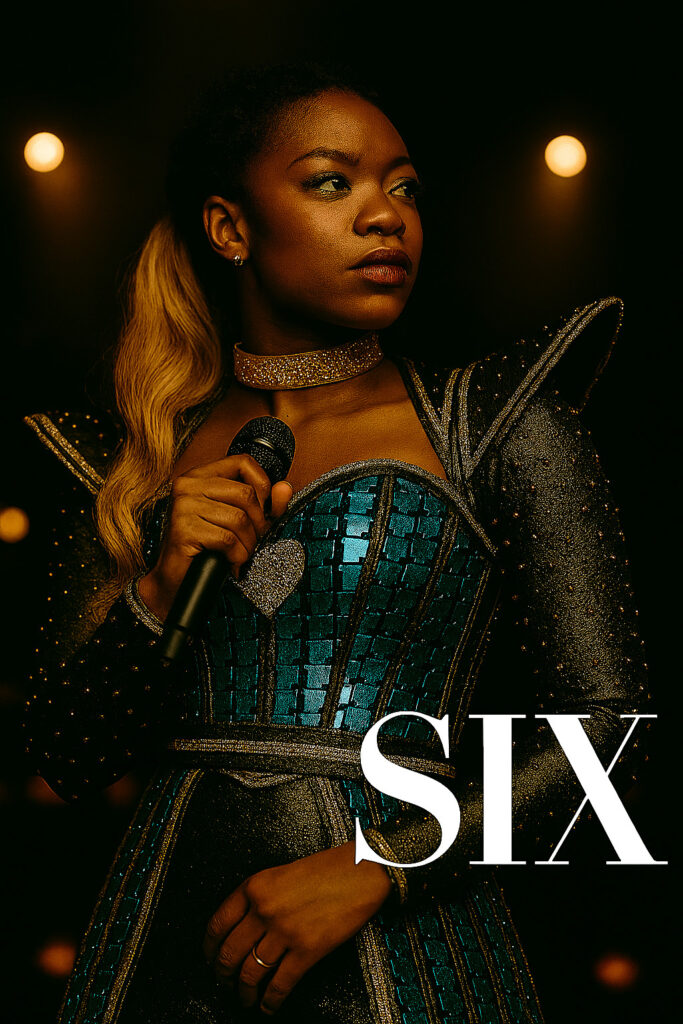

Catherine Parr’s “I Don’t Need Your Love” renounces both the contest narrative and Henry. Her role, inspired by Alicia Keys and Emeli Sandé, is that of a mature, compassionate, quietly powerful leader, who gently but firmly brings the group together for their climactic “happily ever after” re-imagining.

Creative Liberties and Analysis

In the stage show, Parr’s identity as an intellectual, reformer, and carer for Henry’s heirs is highlighted, but many details—her political negotiations, the complex, at times traumatic, post-Henry years with Thomas Seymour—are compressed. Still, the musical’s respect for the fullness of her identity, and the decision to have Parr “end the contest,” feels justified. Her real-life advocacy for all three children’s succession and her publication record is a rare triumph for a Tudor queen, honored by the musical’s final chorus of shared solidarity, not rivalry.

“Don’t Lose Your Head”: A Modern Classic – Lightheartedly

It would be criminal not to celebrate “Don’t Lose Your Head”—Anne Boleyn’s tongue-in-cheek, TikTok-viral, boundary-breaking showstopper. Andrea Macasaet’s interpretation, from her first entrance making mischief to the sidesplitting physical bit when she playfully pantomimes a historically infamous event, is legendary for good reason. Her delivery brings sly meta-winks, mischievous innocence, and all-out joy to what could be a mere litany of courtly intrigue. In every handspring, bounce, and well-timed comedic beat, she makes Anne’s fate both deeply felt and laugh-out-loud funny—proof that comedy and tragedy, with the right performer, are not opposites but intimate partners on the musical stage.

Artistic Liberties, Anachronism, and the Power of “Historemix”

SIX does not exist to set the historical record straight; rather, it exists to *rewrite the cultural script*. The creative team acknowledges their blend of fact, fantasy, and pop culture is intentional—a spark for conversation, not a substitute for biography.

Major Artistic Choices:

– Modern Dialogue & Technology: References to “messaging every day,” “going viral,” and dating apps (“Haus of Holbein”) transplant the queens’ emotional realities into the language of Instagram and TikTok, without pretense of period accuracy.

– Stereotype as Satire: Rather than shying away from iconic imagery—the six-finger myth, Anne’s “green sleeves”—SIX pokes fun at the long shadow of pop-history mythmaking, subverting old narratives for laughs and insight alike.

– Musical Characterization: The use of contemporary musical styles, from intimate ballads to hip-hop bangers, is a deliberate anachronism, prioritizing character over replication. Each queen’s style introduces emotional resonance for modern audiences.

– Feminist Message: Central to the show is the reframing of female suffering—not through competition, but through solidarity. The finale’s group anthem reimagines a world where each queen shapes her own destiny, leaving “his-story” for “her-story”.

While several biographical details are streamlined or omitted for clarity and pacing, the arc of each queen’s story remains recognizable. The showtriumphs in generating interest in these historical figures, as evidenced by the uptick in Tudor history discussions on social media and among younger fans.

Performance and Reception: Humor, Heartbreak, and Empowerment

SIX is, at its best, a masterclass in theatrical juxtaposition, fusing trauma with comedy, heartbreak with empowerment. Its approach is joyful, unapologetically anachronistic, and deeply resonant with modern feminist themes—a sentiment echoed by critics and historians alike.

Critical and Audience Voices

– Inventiveness and Ensemble: Critics consistently highlight the inventiveness of Marlow and Moss’s score and script, the “powerhouse” cast performances, and the exhilarating stagecraft of its innovative design and choreography.

– Comedic and Dramatic Tone: Reviewers praise the production’s ability to oscillate between wicked humor and earnest drama, especially in pieces like “All You Wanna Do,” where comedy gives way to searing critique.

– Feminist Subtext: The show’s “take-down of the patriarchy,” as one critic put it, is carried by both script and performance, with young audiences particularly moved by the diversity, sisterhood, and agency displayed on stage.

Not every reviewer is uniformly convinced by the depth of the show’s feminist message; some wonder if its catchy tunes and glitzy visuals sometimes overwhelm its more substantive ambitions. But most agree that, as an entry point for further inquiry and as an energizing piece of pop theater, it is uniquely effective.

Conclusion: SIX’s Throne in Contemporary Musical Theatre

In sum, SIX is that rare unicorn in musical theatre: a show that marries historical context and pop-cultural inventiveness, making centuries-old figures feel fresh, relatable, and endlessly discussable. Its artistic liberties—whether presenting Anne Boleyn as an antihero party girl, giving Anne of Cleves a pop-culture victory lap, or re-centering Katherine Howard’s tragedy

through a MeToo lens—are not accidental, but part of a creative strategy that values emotional impact, humor, and empowerment alongside truth.

Andrea Macasaet’s Anne Boleyn is, for many, the crown jewel of this approach—her comedic luster and emotional complexity ensuring that Anne’s “second place” is really first in our hearts. But the show’s true legacy may be its ability to spark new curiosity, debate, and creative thinking about the real women behind the rhyme: divorced, beheaded, died; divorced, beheaded, survived.

SIX invites us to remember, reimagine, and celebrate these queens—not as mere wives, but as vibrant, complicated, unforgettable individuals. And maybe, just maybe, to lose our heads with joy in the process.